Ridley Scott is one of the most consistent filmmakers in Hollywood. Not consistent in quality film output (Scott is often a boring filmmaker) but consistently technically competent. He is a master of the technical art of cinema yet not exactly a filmmaker capable of making good movies prolifically.

Across his long career, Scott has never made an entirely bad film. His direction is always exact and extremely versatile; Scott is the only director who can competently direct any genre, except probably rom-coms, though his competency often makes dull cinema.

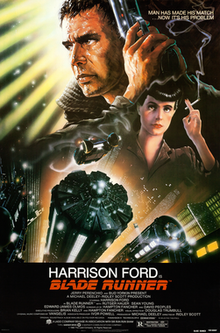

In his long career, Scott has made a handful of good movies. Yet, only three are the sort of juggernauts that his reputation suggests: the classic horror film Alien, the progressive thunderbolt of a road movie Thelma and Louise, and Blade Runner, the most visually brilliant picture to come out of a Hollywood studio.

Blade Runner’s plot, loosely based on an excellent novel by Philip K. Dick, follows Rick Deckard, a burnt-out cop who specializes in tracking down and “retiring” androids who have gained sentience, a so-called Blade Runner. After an android shoots another Blade Runner, Deckard is tapped to track it‒and three others it appears to associate with down.

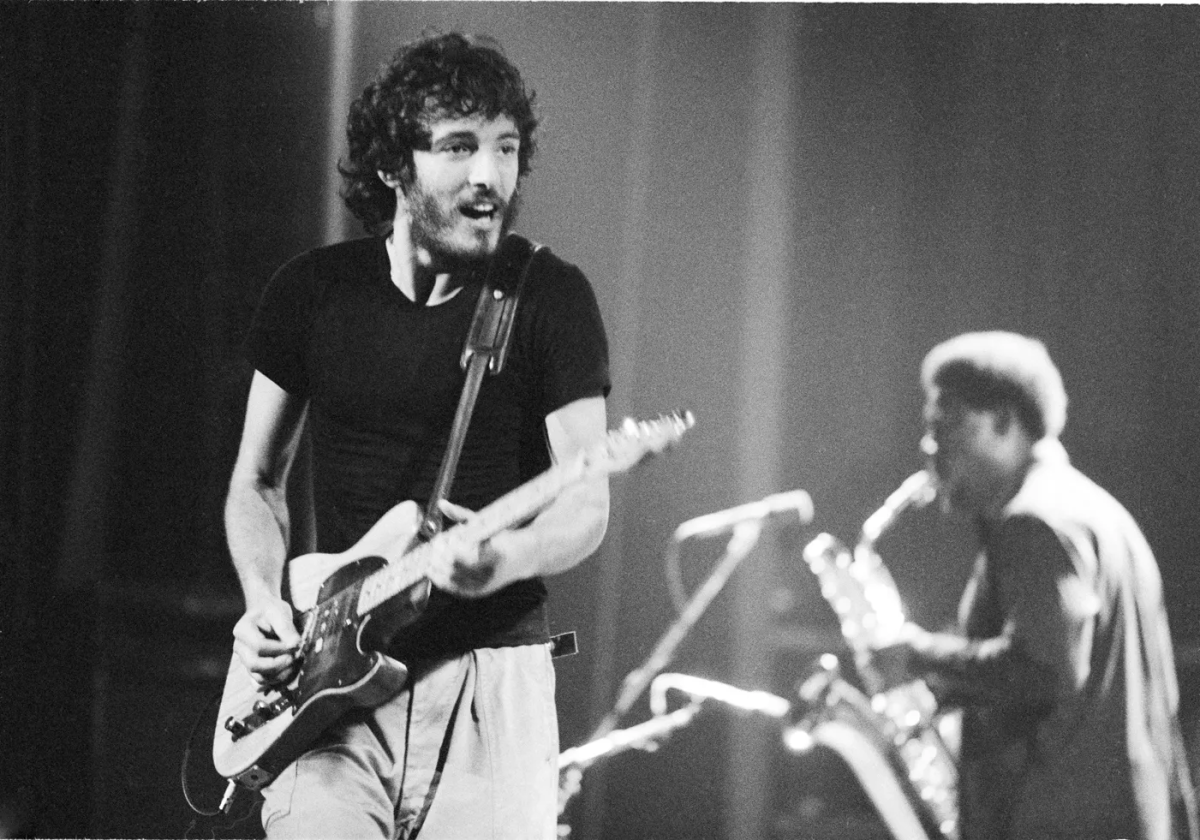

For a sci-fi film, the acting is top-notch. Rutger Hauer’s performance as Roy Batty, the main android, has become the standard of a humanlike machine displayed in fiction. Harrison Ford gives the best performance of his career.

The bulk of Scott’s early experience as a director came through advertisements, and the eye needed to catch mindless television audiences finds its way into his camera work. Frequently across his filmography, though especially in Blade Runner, Scott employs lighting effects and copious amounts of smoke to fill the frame for no apparent reason besides aesthetics. Yet these flourishes are only the outer layer of Scott’s early craft. Scott is so proficient in visual storytelling that he affords himself a degree of flash. What separates Scott from a flashy hack, like Zach Snyder(300, Watchmen, Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice) or Robert Rodriguez(From Dusk Till Dawn, Sin City with Frank Miller, Alita: Battle Angel), is his ability to use his flash as flourishes.

Since 1991, Scott has seemed like a shell of himself. Scott is still extremely consistent, his films aren’t particularly messy, but now they’re boring. Around the time digital CGI became prevalent, filmmakers known for special effects were forced to adjust the type of films they made or become outdated. While Steven Spielberg, James Cameron, or George Lucas could adapt, filmmakers like Ridley Scott or John Carpenter couldn’t. Carpenter was smart and retired, but Scott decided to keep working. The highlight of Scott’s craft, his flash, is stuck thirty years in the past though his storytelling skills allow him to still work with dull, surgical proficiency. Ridley Scott is a relic of the eighties.

Gladiator 2, releasing later this year, could be a return to form for Scott, though I strongly doubt it. I hope he proves me wrong.

Blade Runner is a look at everything Ridley Scott has lost, and oh is it brilliant.

Blade Runner is available anywhere movies are rented and at the Broomfield Public Library. Be sure to watch The Final Cut. The other cuts are dramatically worse.