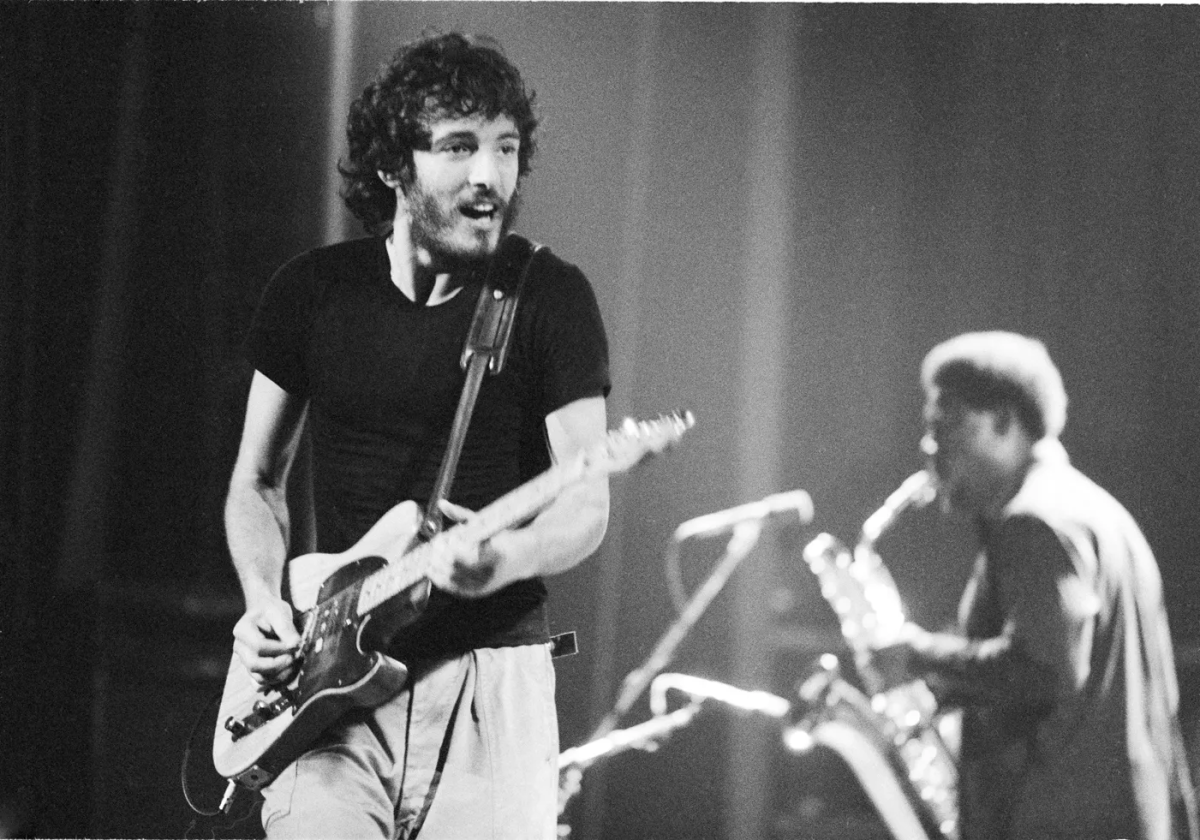

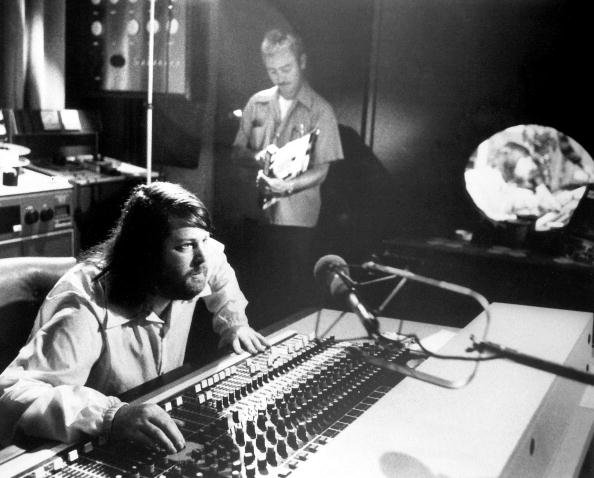

If one flips to the glossary in a book about music production, odds are, the terms found will originate from one of three 60s pop producers: George Martin, who arranged nearly all string and horn sections and produced practically all songs across The Beatles’ recordings; Phil Spector, who pioneered the Wall of Sound style imitated by thousands of artist ranging from The Velvet Underground to Bruce Springsteen; and, finally, Brian Wilson, the creative head of The Beach Boys.

Wilson’s most significant achievements are much smaller in volume than Martin’s or Spector’s, primarily due to longevity. Brian Wilson had complete control over one album, Pet Sounds. Every prior Beach Boys album was commercially focused and lacking in the brilliance of Pet Sounds: every album after attempted to piece together the aspects that made Pet Sounds brilliant.

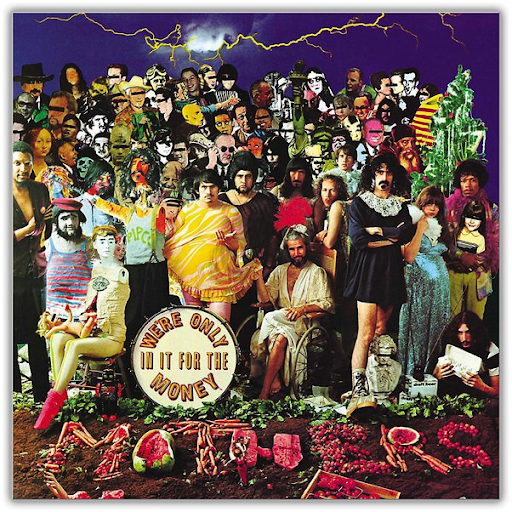

Well then, what made Pet Sounds so brilliant? Up until the release of this album, most non-jazz albums existed to sell a few singles a second time and were filled with “filler”; Pet Sounds, along with albums like Rubber Soul by The Beatles and Bob Dylan’s Electric trilogy, helped establish the idea that an album can be a cohesive work of art, free of “filler,” thus beginning the album era.

Pet Sounds also introduced the concept of using the recording studio as an integral part of recordings: Pet Sounds is the first album that could be considered overproduced because, to that point, vapid, gaudy production was unfathomable, as was recording an album with a legion of studio musicians that vary from song to song. Wilson’s pop masterpiece recreated the music industry from scratch. Yet, the most compelling part of a good pop album is, and will always be, quality pop songwriting and composition, of which Pet Sounds is nearly unmatched.

In topping Pet Sounds, Wilson had created an inevitably impossible challenge, though an attempt was made. Wilson spent the better part of 1966 recording one song, Good Vibrations: this was, at the time, the most expensive song ever recorded.

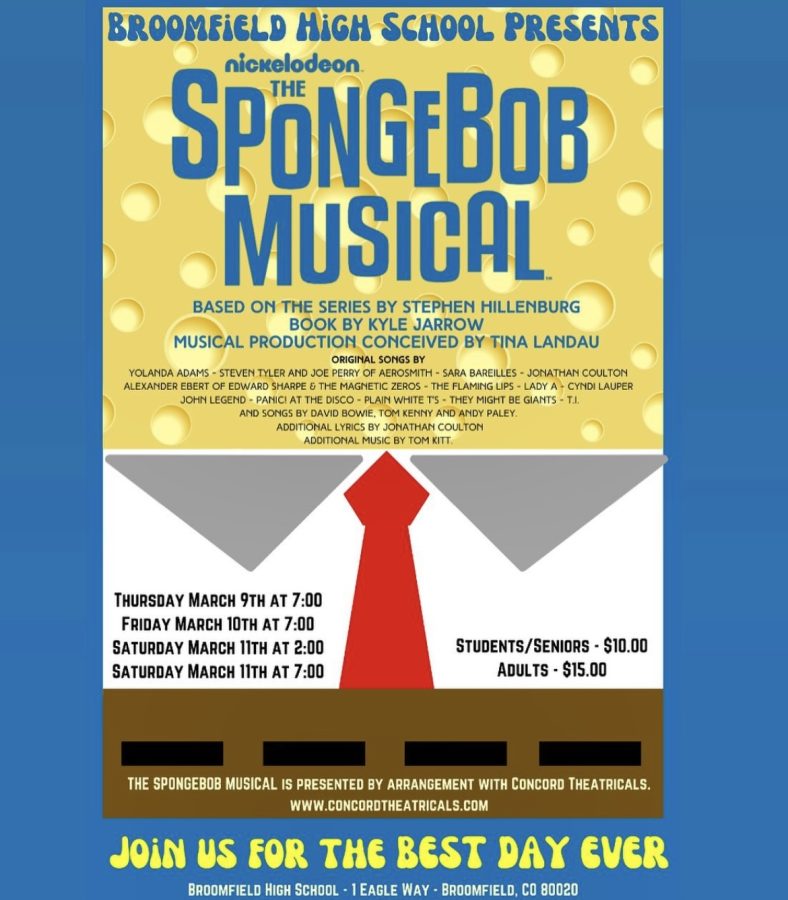

Wilson planned to include Good Vibrations on an album called Smile. If one opens The Beach Boys’ Spotify page and scrolls through to the albums from the ’60s, there is no Smile; instead, there is 1967’s Smiley Smile. These two albums are not the same. Smile was released in fragments periodically from the late sixties on. Smiley Smile is itself a fragment.

The public was never informed why Smile was never finished. There is a theory: Smile was shelved because Mike Love and the other Beach Boys failed to see Wilson’s vision; I think this is false because of clear evidence that Wilson himself shelved the project.

Wilson tended towards self-destructive perfectionism throughout his entire career, but in 1966-67, Wilson began experimenting with drugs and saw his mental state further plagued by his Bipolar and Schizoaffective disorders. Wilson saw a vision and tried to fly up to reach it, only to find his wings were made of wax. Upon realizing this, he returned to the realm where he could fly comfortably, if not daringly.

Smile died because of creative burnout and record label demands, not because of some plot from the other Beach Boys. Brian Wilson soon became less involved with The Beach Boys; Bruce Johnston would classify him as a “visiter” in sessions for later albums.

The late 60s and early 70s saw The Beach Boys repeatedly disgrace themselves, ultimately fading from the public eye. Fragments of Smile appeared on several albums around this time: Smiley Smile included Good Vibrations and Heroes and Villains: 1971’s Surfs Up’s title track was initially composed for Smile.

Fragments of Smile were kept alive through another, now-defunct, music industry staple: bootlegs. By some likely elicit means, individuals acquired fragments of Smile and recorded them on tapes to share. By the mid-eighties, several bootlegs claiming to be Smile circulated the globe. A bootleg from Japan is said to have included a 15-minute version of Good Vibrations.

Smile will never be released. Wilson created an imitation in the early 2000s called Brian Wilson Presents Smile, but Wilson has said in interviews that this version differs from what he would have made in the 60s. The closest we will get to Smile is 2011’s The Smile Sessions. These recordings, while fantastic, are unfinished.

Making music is hard. Making music in the mid-sixties was harder. What Wilson accomplished in the 60s is legendary, whether all of it was released or not. The endurance of Smile stands as a testament to the charm of The Beach Boys, not the creative failings of the band’s leader.