Ahead of Their Time: How Underground Rock Bands Changed Music

Much of the punk and pop music you’ve heard, from Weird Al to R.E.M, come from the same lineage.

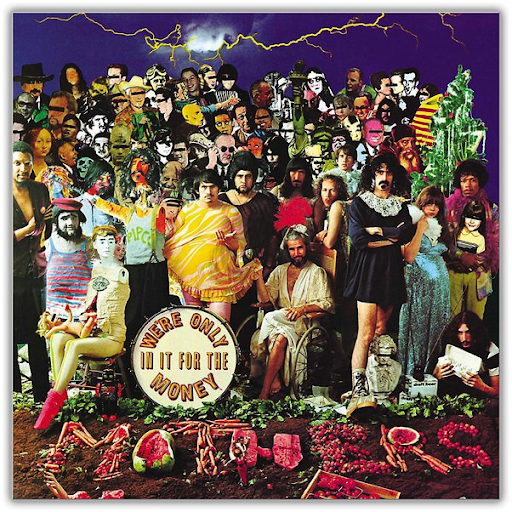

Cover for Frank Zappa’s 1968 album: We’re Only in it for the Money.

April 11, 2023

The 1960s contained the most significant cultural shift in post-war America. Many of the central figures of the transition were Brits and Californians on hard drugs and hallucinogens making music, some of which were good. While bands like The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Jimi Hendrix Experience created the most influential music of the period in the mainstream, much of the most meaningful developments occurred underground in local art scenes.

These underground groups tended to conduct more radical experiments than their mainstream contemporaries and scared more traditional audiences. These underground experiments largely dodged fame, though they influenced the right people.

One of the earliest major underground experiments was The Velvet Underground.

The Velvet Underground was born out of New York’s art scene; guitarist and songwriter Lou Reed, multi-instrumentalist John Cale, guitarist Sterling Morrison, and drummer Moe Tucker rounded out the band’s core lineup.

The Velvet Underground was one of Andy Warhol’s pet projects for much of the 1960s. The Velvet Underground’s core lineup entered the studio for the first time in April 1966; Warhol brought German singer Nico onto these recordings. What resulted was The Velvet Underground & Nico, referred to as “The Banana Album” for the Warhol album cover.

Despite mixed reviews and selling a meager 30,000 records upon its release, The Velvet Underground and Nico developed a massive cult following. Legendary music producer Brian Eno said, “Everyone who bought it formed a band.” Rolling Stone ranked The Velvet Underground and Nico 23rd in their 2020 Greatest Albums list.

The Velvet Underground would make one more album with their core lineup, White Light/White Heat, before John Cale left the band due to creative differences with Reed.

Many of the experimental ideas the band tried on their earlier albums come from Cale. After his departure and Reed’s ascension to band leader, Reed led the band in a somewhat more conventional direction while keeping The Velvet Underground’s signature experimentation.

The remaining core members, plus new-hire Doug Yule to replace Cale, recorded two excellent studio albums, The Velvet Underground and Loaded, and a live album before Reed, Tucker, and Morrison left the band. Yule attempted to continue The Velvet Underground with an album, Squeeze, in 1973 but met with poor reviews and worse sales.

What Yule achieved with Squeeze is impressive; he somehow failed to replicate The Velvet Underground’s sound while failing to do anything new or engaging. Despite whatever criticism Squeeze gets, it still is a professionally recorded, produced album; that is more than most bands can claim.

The Velvet Underground’s sound changed between albums. The Banana Album and White Light/White Heat are wildly innovative spiraling melodies of fuzz, The Velvet Underground is mellow and lyrically brilliant, and Loaded is more conventionally hit-driven.

David Bowman of The New York Times called The Velvet Underground “arguably the most influential American rock band of our time.” Their influence is front and center in the punk and alternative music of the seventies, eighties, and nineties.

At the same time, another experimental band was making waves in California. This band was called The Mothers of Invention.

The Mothers started as a local band, then named The Soul Giants, playing small clubs. When the guitarist quit, everything changed for the group; this opened the doors for Frank Zappa, a mountain of hair with a mustache and an immense talent for guitar, to join the band.

Zappa soon took over as band leader, convinced the band to play his original music, and took complete creative control over the group. The band had its live debut on Mother’s Day, 1964; soon after, the band changed its name to The Mothers of Invention.

The Mothers slowly gained attention in the Los Angeles underground scene, ultimately earning a record deal with Verve Records. The Mothers’ first studio album, Freak Out!, was released in 1966. This album was one of the first studio double albums.

By the time the band’s second album (Absolutely Free) was released, The Mothers had obtained a decent following.

In late 1966, The Mothers signed a contract with the Garrick Theater in New York to play regular shows for six months; this triggered the band to move from the west coast to the east coast.

In New York, The Mothers recorded their third album; We’re Only In It For The Money. The album’s cover art spoofed The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the lyrics viciously satirized the hippie flower power movement. Zappa, throughout his career, gained a reputation as one of the greatest satirists of his time, and much of his most distinguished satire came with his sixties work. The Mothers also released a Doo-Wop album in this period.

In 1968, The Mothers moved back to Los Angeles. At this point, The Mothers had nine members, all paid out of pocket by Zappa; the financial burden ultimately led Zappa to dissolve the band in 1969. Some saw this as Zappa going on an authoritarian power trip though several members continued to play with Zappa. Their final recordings were released in 1970 as Weasels Ripped My Flesh and Burnt Weeny Sandwich.

The sound of Zappa’s early work with The Mothers is full of strange satire, bewitching compositions, and fascinating production, ripples of which are present in anything released after that lingers towards the bizarre.

After the dissolution of The Mothers, Zappa continued to produce music on the same level with varying levels of experimentation.

Zappa is one of the most accomplished guitarists in music history. His brilliance stems from his improvisation; Zappa prided himself on never playing the same solo twice, so all his live shows were drastically different from the last. Rolling Stone ranked Zappa 22nd on their 2015 greatest guitarist list, above legends like Jerry Garcia, Tony Iommi, and Slash.

Two of the most critical events in Zappa’s career occurred in December of 1972; the first was a Zappa concert at the Montreux Casino in Switzerland, where an audience member started a fire that ultimately burned down the casino; this event was the inspiration for Deep Purple’s hit Smoke On the Water. Two weeks after the fire, a fan, angered at his girlfriend’s infatuation with Zappa, shoved Zappa from the stage into the concrete-floored orchestra pit; his band thought Zappa had died. Instead, he suffered severe wounds to his head, back, leg, and neck, as well as a crushed Larynx that permanently dropped the tone of his voice. The second event led Zappa toward his later cynicism.

Zappa would allow his backing bands a certain amount of creative freedom under him until he adopted a more employer/employee relationship in the 70s and 80s.

Zappa would have a long and highly prolific career, always backed by bands full of the world’s most renowned musicians. By the late eighties, Zappa’s bands could play hundreds of compositions in several styles and time signatures at any moment during a performance.

These bands were far from the last underground music experiments. Every alternative rock band, from Nirvana to Sonic Youth to R.E.M., takes something from The Velvet Underground. Zappa-inspired improvised live acts, such as Phish and King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, consistently selling out consecutive nights at massive venues, and Zappa’s experiments have inspired countless other bands; Zappa’s humor could even be considered a principal influence on “Weird Al” Yankovic.

If these underground bands should show you anything, it is that if you make art, you should not worry about being famous; if your art is good, sooner or later, you will get the recognition you deserve.