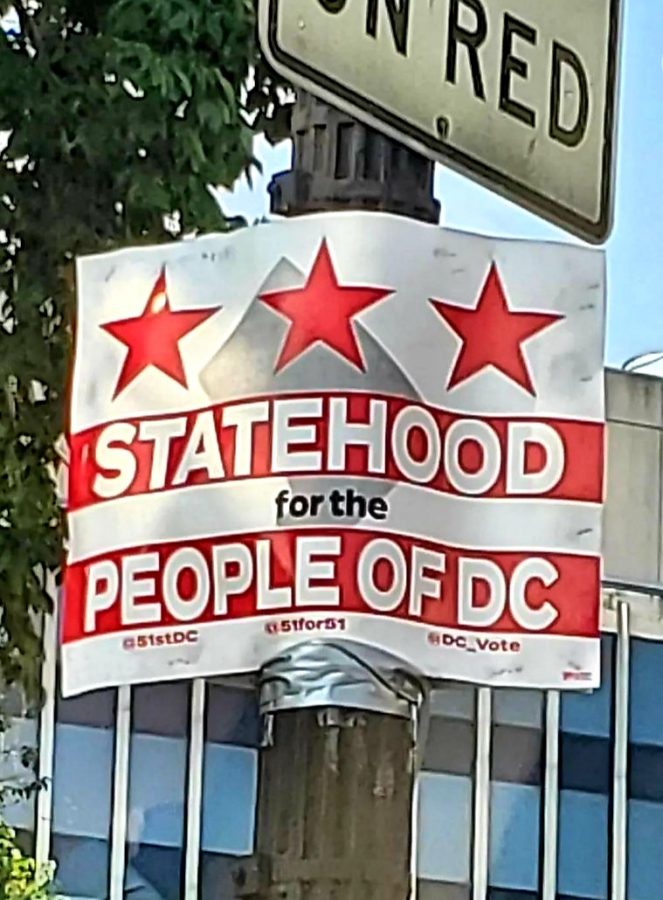

Number 51?

Calls to make Washington, D.C., a state echo in Congress and in the district itself.

December 7, 2021

Washington, D.C., is undoubtedly the hub for political activity. It’s home to Capitol Hill, the White House, and the Supreme Court, centers for each and every branch of American government. It’s also home to over 700,000 people.

These people, along with the district which they reside in, are at the center of H.R. 51, a piece of stalled congressional legislation that, if passed, would make Washington, D.C., a state, the 51st to enter the Union.

What is D.C. statehood?

Whether or not H.R. 51 should be adopted and the District of Columbia should become a state is often referred to as the issue of “D.C. statehood.” Under the bill, (almost) all of the territory currently made up by Washington, D.C., would be given official state status as recognized by the U.S. government.

The exception would be for federal buildings like the U.S. Capitol building, the White House, and the Supreme Court. They would reside in a territory simply known as the Capital and would be excluded from the new state, which according to the bill’s text, would be known as Washington, Douglass Commonwealth—named for Frederick Douglass, a monumentally influential writer and abolitionist.

H.R. 51 passed with 216 votes in the House of Representatives, moving a step in the direction of statehood. However, it, like many other pieces of consequential legislation, is currently stuck in the United States Senate.

Why does it matter?

The idea of D.C. statehood has gained the support of a multitude of national, state, and local entities, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and even Georgetown and American University, two prominent colleges located in the district.

In addition, in 2016, when they were given the opportunity to vote on a ballot measure in favor of petitioning Congress to grant D.C. statehood, nearly 80% of Washington, D.C., voters supported the measure.

Congressional representation

The primary argument in support of statehood can be summarized by a phrase which decorates the bottom of many District of Columbia license plates.

Taxation without representation.

That is to say that, while residents of Washington, D.C., pay taxes just like those living in each of the 50 states, they do not have the same representation in Congress. The 714,153 people living in the district are not represented by any U.S. senators, and their one delegate to the House is unable to vote for or against floor legislation.

This has caused concern and outrage across the country, and many have noted that while states like Wyoming and Vermont have smaller populations than the district does, each still has two senators and an official voting representative in the House to account for every state resident.

If Washington, D.C., was given voting representatives in Congress, it would have a significant effect on the political landscape of the entire country, potentially shifting party power and ultimately impacting Americans in every state.

Racial inequality

Another point at the center of the discussion is the fact that 46% of Washington, D.C., residents are Black (for perspective, about 14% of the whole United States population is Black.) Therefore, it is Black Americans who are being disproportionately left out of congressional representation in the district.

Evidence detailed by New York University Law School’s Brennan Center for Justice shows that Black Americans are being disproportionately disenfranchised by new restrictive voting laws being passed across the country, and the United States has an evident history of disenfranchising and discriminating against marginalized groups in democratic processes.

Because of this history and modern-day prevalence of voter suppression and inequity, many activists and politicians have highlighted the large impact that lack of congressional representation has had on Black Washington, D.C., residents specifically.

What are the arguments against statehood?

While many politicians have come out in support of the statehood bill, many still oppose it. Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) has said that he does not support H.R. 51, but rather a constitutional amendment to grant the district state status. Others have echoed this approach, while a large group remains opposed to statehood altogether.

Lack of historical intent and potential unconstitutionality

Last year, Representative Jody Hice (R-GA) took to the House floor for debate on a version of H.R. 51. One of his primary arguments against statehood, which has been repeated by a multitude of conservative politicians and interest groups across the country, is that state status was purposefully withheld from Washington, D.C., by the Founding Fathers.

“Our nation’s founders made it clear that D.C. is not meant to be a state,” Hice said.

Arguments like his have brought into question the constitutionality of D.C. statehood altogether, though this question of legality is still widely debated.

Political influence

Others in opposition of statehood assert that it’s just a power-grab attempt by congressional Democrats (voters in D.C. lean Democratic.)

In an official April press release, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) said, “Make no mistake about it, H.R. 51 is just Democrats’ latest attempt at a power grab.”

As of right now, 50 of the 100 seats in the United States Senate are occupied by Democrats (the Senate majority is still held by Democrats because the tie-breaker is the vice president, who is currently Democrat Kamala Harris.)

If H.R. 51 became law and two senators from Washington, D.C., were added to the mix, however, the close numbers in the Senate would likely tip more in the favor of Democrats (if current Washington, D.C., voting trends continue).

Will H.R. 51 ever become law?

Even if moderate Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin did support H.R. 51, the bill would not have enough support in the Senate to overcome a filibuster, so it is unlikely that it can pass under current congressional circumstances.

The constitutional amendment path is even more narrow. In order for an amendment to be officially introduced, it must be brought up by a ⅔ vote in both chambers of Congress or by ⅔ of the states. And even if the amendment overcomes those challenging barriers, ¾ of state legislatures must then vote to ratify it. A statehood amendment, right now at least, would not be able to gain that much support.